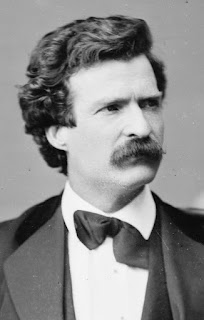

Many years ago Mark Twain wrote a brilliant, humorous essay where he berated the German language for complexity of its grammar. This essay has probably been used as a source of excuses, ever since, by thousands of struggling students of German.

It’s sometimes said that people tend to be either be good at languages or good at mathematics. But what are the differences? Mathematics and physics are only considered to be properly defined when a set of explicit, repeatable rules exist. But the language text books are full of the rules of grammar and probably the biggest challenge in learning a language is learning to ‘internalise’ grammatic structure.

And structure is crucial to communication. In 1948 Claude Shannon produced a milestone study of communication theory, ‘A Mathematical theory of Communication.’ While this was primarily concerned with telecommunications theory - formalising and creating a rule set in order to improve the quality of electronic communication. But some of Shannon’s observations have since been generalised and applied to other forms of communication including spoken and written language.

All communication systems are subject to ‘noise’. In this sense ‘noise’ is interference or corruption of the intended message. Anyone who has tried to follow a discussion on a weak radio channel is aware of the implications of noise. But over the years communications systems have improved because techniques of reducing the effect of noise have been devised.

The protocols of effective and accurate communications require a level of redundancy in the creation of messages. Codes converting letters into numbers have been in use since the 16th century but it was with the invention of the electrical telegraph that message accuracy fell into the province of engineers.

The accuracy of telegraph message communication was greatly improved by adding ‘parity’ bits. By imposing the rule that all alphabetical characters must be encoded with an even number of bits it meant that noise errors that either added or remove a bit during message transmission could be easily detected. The message content was unchanged by these parity bits, they provide only a means of knowing if the message has been received accurately or not. In the event of errors a repeat of the transmission could be requested.

Grammar in human communications performs a similar function. If we have two short sentences:

There is one dog.

There are two dogs.

The fact that the first sentence is speaking of dogs singular is apparent from use of is and the lack of s on the end of dog and the fact that we speak of one. In the second sentence we speak of dogs plural and have the are and the s and the two to confirm that we now refer to more than one dog.

If all communication were to take place in perfect conditions one might argue that two constructions are not needed, the second construction could always be used. Thus, “There are one dogs.” Of course, to an adult native english speaker this introduces a level of cognitive dissonance. We immediately question what we’ve heard and usually request a re-transmission - "excuse me?". Because communications conditions are rarely perfect humans seem to have evolved language in such a way as to support reliable and accurate communication by emphasising the difference between singular and plural. The spoken language has redundancy.

Grammar imposes many more rules. And German grammar, as Twain so memorably recounts, is greatly preoccupied with emphasising the gender of nouns and the four cases: nominative, accusative, dative and genetive. Together the gender of the noun and the usage of the noun in the sentence contrive to modify, amongst other things, the definitive article - THE.

If a sentence such as, ‘The girl gives the teacher the apple’ is translated to German we find three different expressions of the definitive article. : Das Mädchen gibt dem Lehrer den Apfel.

Das Mädchen, the girl (gender neutral, case nominative).

Dem Lehrer, the teacher (gender masculine, case dative).

Den Apfel, the apple (gender masculine, case accusative).

The different expressions of THE add redundancy to the sentence. Even without thinking about the verb too much the proficient listener knows that das Mädchen is the subject of the sentence and den Apfel is the object. The rather unfortunate thing is that the whole construction is made more complicated by needing to consider the genders of nouns. And the choice of gender is, I believe, largely arbitrary.

Native speakers have learned in early childhood how to correctly apply all the rules of whatever language they are born to. They soak up all the genders and internalise the context so that the correct version of the definitive article is used without conscious thought, without any formal expression of rules. For adult students of a foreign language it’s different. There’s vocabulary to learn and one must learn enough about grammar and the structure of sentences to be able to parse and deconstruct the sentences we hear in ‘real-time’.

Through copying it becomes possible to speak original sentences of our own. German is easier to pronounce than english, the sounds the various letters make consistent. Learning pronunciation can be difficult as the larynx frequently needs to learn how to produce different sounds than it is accustomed to but once that’s done you are on your way.

*

But why are some people better at mathematics and some at languages? I think this relates to how these different skills must be learned.

Algebra, for example, is also concerned with the manipulation of symbols according to a set of rules. The difference here being that the ruleset is much smaller than any spoken language ruleset and is totally consistent. The mathematics student learns the structure and the rules and then applies it. It takes practice and rigorous adherence to process. But there’s no need for the algebra student to follow through the workings of the solutions to various problems, he can solve successively more complex equations using always the same rules. And the answer, once it's been found, doesn't change. Algebra requires a simple ruleset that can be applied repeatedly to numerous different problems.

Achieving proficiency in language is different. One may, for example, hear a sentence and know only 75% of the words with certainty and many words do not have a one-to-one equivalent in your native tongue. If you hear the same sentence again you may figure out more as you recognise a long compound word or a noun derived from a verb that you know. Hear the sentence yet again and you may fill in still more of the blanks. In fact you may settle on the meaning of a sentence and hear it again a month later and have a new insight into its subtlety, perhaps now you recognise an undercurrent of irony that you missed before. Through these iterations the sentence hasn’t changed but you have!

By now you may even feel confident enough to express an opinion on the matter. If you are lucky you’ll have enough words in your vocabulary to express what you want to say. In some ways speaking for yourself is a little easier, you are able to work with the words you know which is not the case when listening.

So, if you are the type of person who only feels comfortable with a limited, highly specific ruleset that you are sure you have completely internalised then mathematics is the topic you will learn more easily. If, on the other hand, you are prepared to ‘have a go’ on the strength of incomplete data, and be prepared to commit to a solution on the strength of it, languages will suit you better.

*

There is a difference between what is known and what can be expressed. You may know how to ride a bicycle but try using english or any other language to tell someone else how to do it. But could it be that some spoken languages are just better for communication than others?

Such matters might be analysed mathematically by evaluating how much of a spoken language is given over to redundancy and how much to carrying the primary information, the payload. As the communication environment changes the necessity for high levels of communication redundancy may change. Perhaps less redundancy is needed. Then certain language characteristics may become just be an unnecessary burden. Like the human appendix, an organ that exists but no longer serves any useful function.

Perhaps the gender of nouns, which appear to carry zero information while imposing complexity to no purpose, may do nothing more than impose a ‘clunkiness’ to the language that actually stands in the way of effective communication.

While not wishing to supply nationalistic chauvinism with any more ammunition, could it be that some human languages are just better than others? In literature and in popular music the english language dominates. Is this merely down to widespread usage or might it be attributed to the inherent efficiency of the english language as a means of expression?

For example, there's a famous english sentence that summarises the dilemma of human existence in ten simple words. Shakespeare asked what we are to make of human evolutions greatest achievement - consciousness.

He poses the question, this remarkable attribute, consciousness, with the pain that self-knowledge brings, is it worth the price? Or, as the man himself put it, “To be or not to be. That is the question.”

*

Good job. You've expressed many of my experiences from my ongoing battle with French (the language).

ReplyDelete